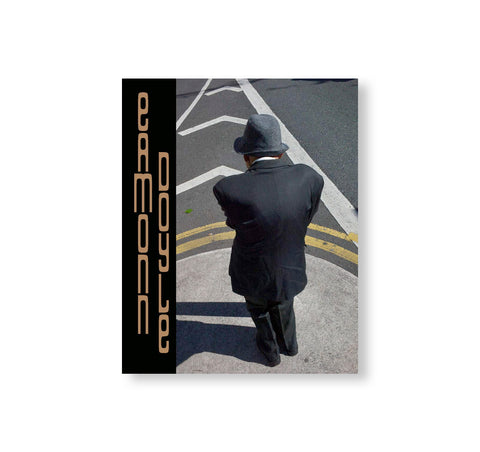

K by Eamonn Doyle [SIGNED / NUMBERED]

アイルランド人フォトグラファー、イーモン・ドイル(Eamonn Doyle)の作品集。作者の兄の急逝による母の痛哭を描く一冊。

「ダブリン三部作」である『i』(2014年)、『ON』(2015年)、『End.』(2016年)において、作者は目の前で繰り広げられる都市の動きとそこで暮らす人々の行動を切り取った。本作では、ダブリンが位置する東海岸の都市部から離れ、アイルランド西端の大西洋沿岸へと舞台を移し、ところどころでどこからともなく現れる、人間の手が全く加えられていないパラレルワールドのような風景を訪れた。

我々は強烈な色彩で描かれた写真を通し、この風景を旅しながら自在に姿を変える一人の人物を追うこととなる。布で全身を覆われたその姿は亡霊のようであり、重力、風、水、光に押されたり引かれたりするにつれ、色や質感が変化していく。 ある場面ではほとんど気体のように見え、また別の場所では溶けたように見え、そして時には地に縛られているその重みが見えてくる。そのようなカラー写真とともに、ある種の地震の形跡を描写しているかのように感じさせる、濃いモノクロ写真も多数掲載されている。

本書には、母親が他界した息子に宛てて記した手書きの手紙を何ページにもわたって収録しており、まるで層を成すように綴じられている。作者の兄であるキアラン(Ciarán)は1999年に33歳で急逝した。母親のキャサリン(Kathryn)は2017年にこの世を去るまで、このような時間反転的な出来事による悲しみから逃れられなかった。手紙からはところどころに単語らしきものが読み取れるが、その蓄積によって、楽譜、音波のヴェール、嘆きの音声による譜面として現れるのだ。

ミュージシャンのデイヴィッド・ドノホー(David Donohoe)は、1951年にアイルランドで録音された「キーン(Keen / ケルトの弔いの歌)」をもとに、展示作品群に伴う2部構成の新作声楽曲を作った。この曲は10インチのレコードとして書籍に収められている。この重層的で変化し続ける構成は、本書を体験するにあたり不可欠な部分を成し、その形式と表現方法の両面で書籍本体へ直接的に関わってきている。「キーン(またはアイルランド語の「caoinim」から由来する「Cine」、「嘆き悲しむ」の意)」は、死者のために歌われる古代アイルランドに伝わる嘆きの歌であり、死者の魂をあの世へと導き、集まった人々の悲しみを浄化する表現として存在する。伝統的に「キーン」は女性によって故人の亡き骸のすぐ傍で歌われる。本書に収録する作品の中には、風に揺れる人物と布の歪んだ形が、泣き叫ぶ音そのものの形をしているように見える。

ダブリン三部作において作者は、いかにしてその都市の現代的な力と人々の動きが、絶えず互いに影響しあい、形作るのかを観察している。本作では、我々を形作り突き動かしてきた、根源的かつ原初的な力を探る。

光の速さというのは残酷なもので、我々が振り返ることができるのは常に過去のみであるということだ。遠くを見れば見るほど、より遠い過去を見ることになる。しかし、理解しようと試みることで、過去は現在にもたらされる。たとえ、時にはそうできないことがあるとしても。これは、ダブリンの街角で撮影された写真にも、遥か遠く離れた銀河のプラズマ雲を撮影した写真にも当てはまることだろう。そして、時間の振動を通過することで、どこか理解することができる。まるで、宇宙に放たれた歌のように。

EXHIBITION

KYOTOGRAPHIE

International Photography Festival 2025

会期:2025年4月12日(土)- 5月11日(日)

詳細

※本展は終了いたしました

K

会期:2025年4月12日(土)- 5月11日(日)

時間:10:00-17:00

休館日:4月16日、23日、30日、5月7日

開催場所:東本願寺 大玄関

詳細

※本展は終了いたしました

In his Dublin trilogy (i, ON and End.) Eamonn captured the combined actions of the city and its population as they played out in front of him. With K, he moves away from the urban east coast to the western Atlantic edge of Ireland, to a landscape that, in places, appears out of time, a parallel world untouched by human presence.

Through the intense colour images of K, we follow a figure that shape-shifts as it travels across this landscape. Entirely veiled in cloth, the figure is spectral, changing in colour and materiality as it is pushed and pulled by gravity, wind, water and light. In places it appears almost gaseous, in others it is molten and then, at times, the weight of being earthbound becomes apparent. Accompanying these colour images, K includes a number of dense black and white photographs that appear to describe some kind of seismic evidence.

Printed on a number of pages in the book are stratified layers of hand-written letters from a mother to her dead son. Eamonn’s brother, Ciarán, died suddenly at age 33 in 1999. His mother, Kathryn, never managed to escape the grief of such a time-reversed event, right up until her own death in 2017. In the letters, we can make out a word here and there, but the cumulative effect is their appearance as musical notation, a veil of sound waves, a phonetic score for lament.

Working with a 1951 recording of an Irish Keen, musician David Donohoe has composed a new, two-part piece for voice that accompanies this body of work for exhibition, and is included in the book as a 10" vinyl record. This layered and ever-changing composition forms an integral part of our experience of K, relating directly to it in both form and expression. The Keen (or Cine, from the Irish caoinim, “I wail”) is an ancient Irish tradition of lamentation songs for the dead, to carry their spirit over to the other side and to act as a cathartic expression of grief for those gathered around. Traditionally Keens are performed directly over the body of the deceased by women. In some of the images of K, the contorted and wind-blown shapes of the figure and cloth seem to take on the form of the wailing sound itself.

With his Dublin work, Eamonn looks at how the contemporary forces of the city and the movement of its people continually shape each other. In K, he seeks out the primal, even primordial, forces that have sculpted and driven us into being.

The cruelty of the speed of light is that we can only ever look back in time. The further we look out, the further back in time we see. But this does bring the past into the present as we attempt to understand, even though sometimes we just cannot. This is as true of a photograph taken on the streets of Dublin as it is of one taken of plasma clouds in distant galaxies. And we can only comprehend any of this by passing through the vibrations of time, like a song cast out to the cosmos.

![K by Eamonn Doyle [SIGNED / NUMBERED]](http://twelve-books.com/cdn/shop/files/1_8d35c97d-c833-4b91-8970-c57434c432c2.jpg?v=1740875313)

![K by Eamonn Doyle [SIGNED / NUMBERED]](http://twelve-books.com/cdn/shop/files/2_b2c85727-649a-4bc7-9f15-1f5b600f2c7b.jpg?v=1740875314)

![K by Eamonn Doyle [SIGNED / NUMBERED]](http://twelve-books.com/cdn/shop/files/3_5a10400f-f94f-4206-a466-b24f5255663f.jpg?v=1740875313)

![K by Eamonn Doyle [SIGNED / NUMBERED]](http://twelve-books.com/cdn/shop/files/4_43dbb4a4-e749-4322-985b-31e3aa41b8f8.jpg?v=1740875314)

![K by Eamonn Doyle [SIGNED / NUMBERED]](http://twelve-books.com/cdn/shop/files/5_baaa7378-7372-45d3-b0b7-4634689874a8.jpg?v=1740875314)

![K by Eamonn Doyle [SIGNED / NUMBERED]](http://twelve-books.com/cdn/shop/files/6_40df8017-39d7-4b2f-b8e8-2b4f041ffae6.jpg?v=1740875314)

![K by Eamonn Doyle [SIGNED / NUMBERED]](http://twelve-books.com/cdn/shop/files/7_87b53cfc-933d-4f55-8adb-61b7f5285189.jpg?v=1740875314)

![K by Eamonn Doyle [SIGNED / NUMBERED]](http://twelve-books.com/cdn/shop/files/8_979badf4-c496-4495-9e68-e02d68c1a7ec.jpg?v=1740875314)

![K by Eamonn Doyle [SIGNED / NUMBERED]](http://twelve-books.com/cdn/shop/files/9_2c61a2ba-8f76-4fd5-9a8e-d3a7814df742.jpg?v=1740875314)

![K by Eamonn Doyle [SIGNED / NUMBERED]](http://twelve-books.com/cdn/shop/files/10_2d39617e-96ff-40fd-9a2f-1777a03194e5.jpg?v=1740875314)

![K by Eamonn Doyle [SIGNED / NUMBERED]](http://twelve-books.com/cdn/shop/files/11_e1251bbb-2500-439c-a53d-5a3269a01ae4.jpg?v=1740875314)

![K by Eamonn Doyle [SIGNED / NUMBERED]](http://twelve-books.com/cdn/shop/files/12_c766aa44-5147-48c4-8858-5f9bbf4fd8d0.jpg?v=1740875314)

![K by Eamonn Doyle [SIGNED / NUMBERED]](http://twelve-books.com/cdn/shop/files/13_6cc6a8ee-9d2d-4d0d-a04c-70c01ff9e2e6.jpg?v=1740875313)

![K by Eamonn Doyle [SIGNED / NUMBERED]](http://twelve-books.com/cdn/shop/files/14_394bdfb9-0cc5-4054-859e-accbb00ea134.jpg?v=1740875313)

![K by Eamonn Doyle [SIGNED / NUMBERED]](http://twelve-books.com/cdn/shop/files/15_83028216-d0a0-4980-bb8e-760d889c751f.jpg?v=1740875314)

![K by Eamonn Doyle [SIGNED / NUMBERED]](http://twelve-books.com/cdn/shop/files/16_f8458aee-442b-4207-95ea-d1f99bc29999.jpg?v=1740875314)

![K by Eamonn Doyle [SIGNED / NUMBERED]](http://twelve-books.com/cdn/shop/files/17_9fe3fd7c-849e-47f0-9228-07d0442eda6b.jpg?v=1740875313)

![K by Eamonn Doyle [SIGNED / NUMBERED]](http://twelve-books.com/cdn/shop/files/18_26d76978-6ebb-4541-aefe-f76672cea25a.jpg?v=1740875314)