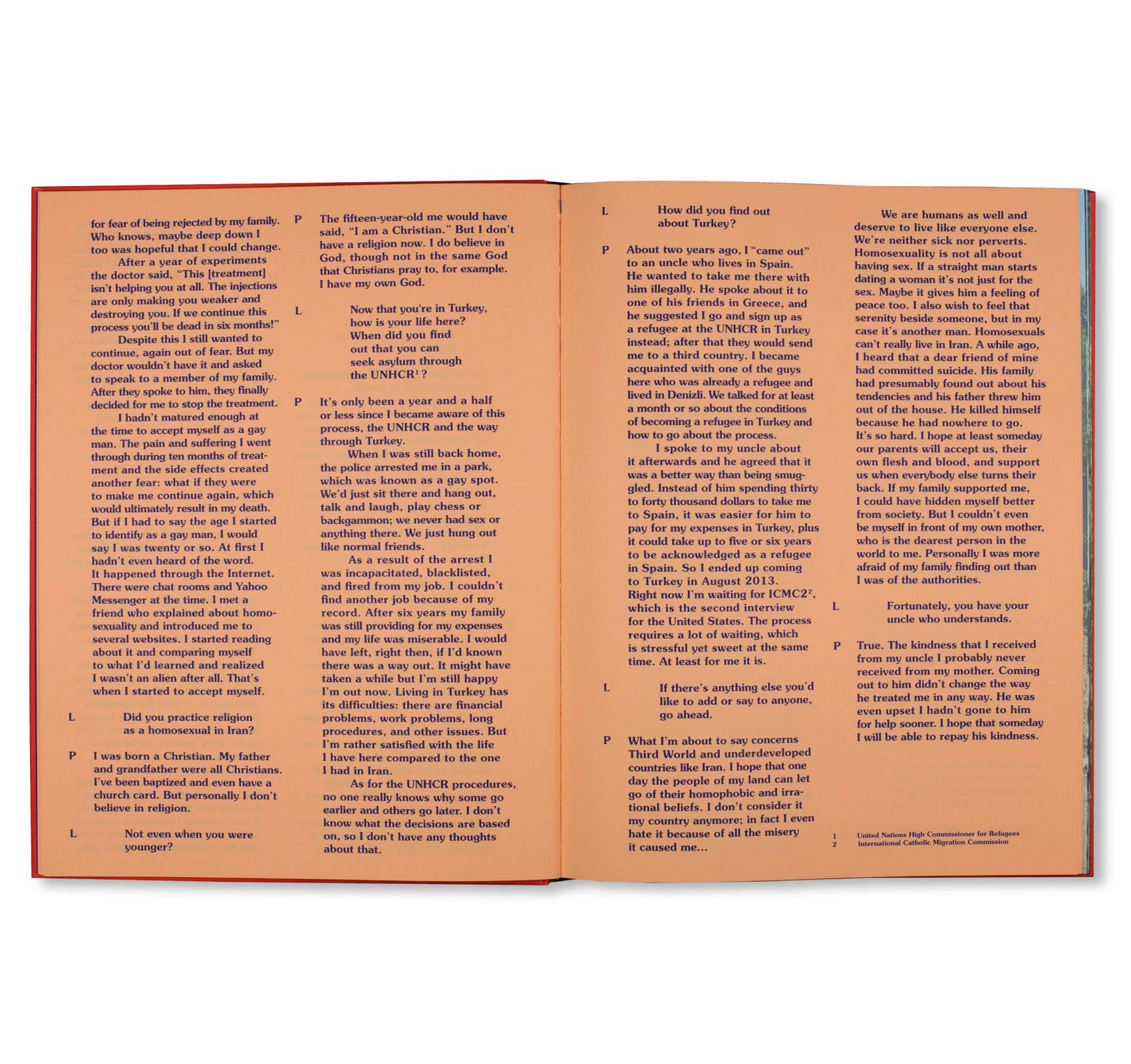

THERE ARE NO HOMOSEXUALS IN IRAN by Laurence Rasti

イラン人の両親を持ちスイスで育ったフォトグラファー、ローレンス・ラスティ(Laurence Rasti)の作品集。

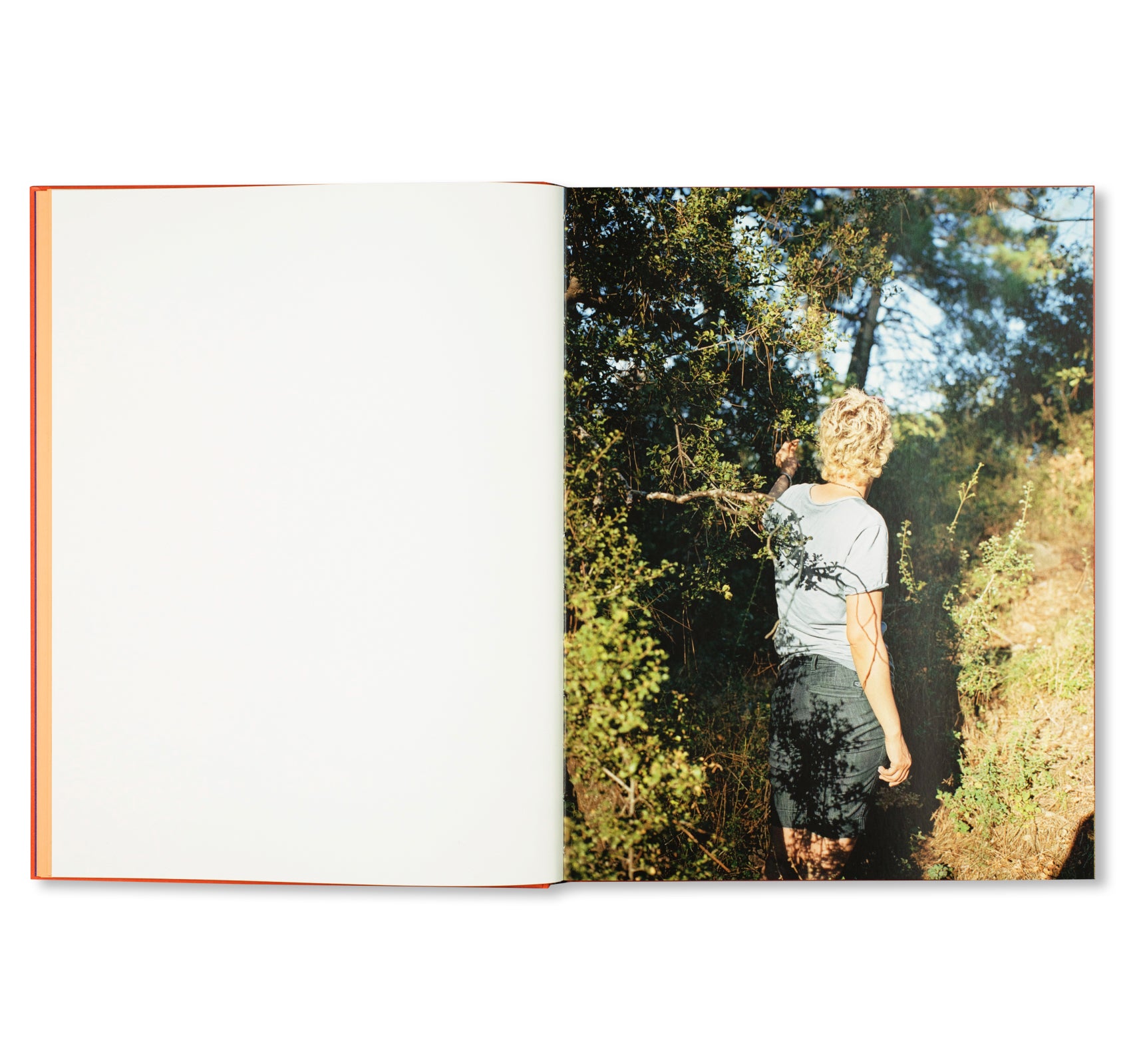

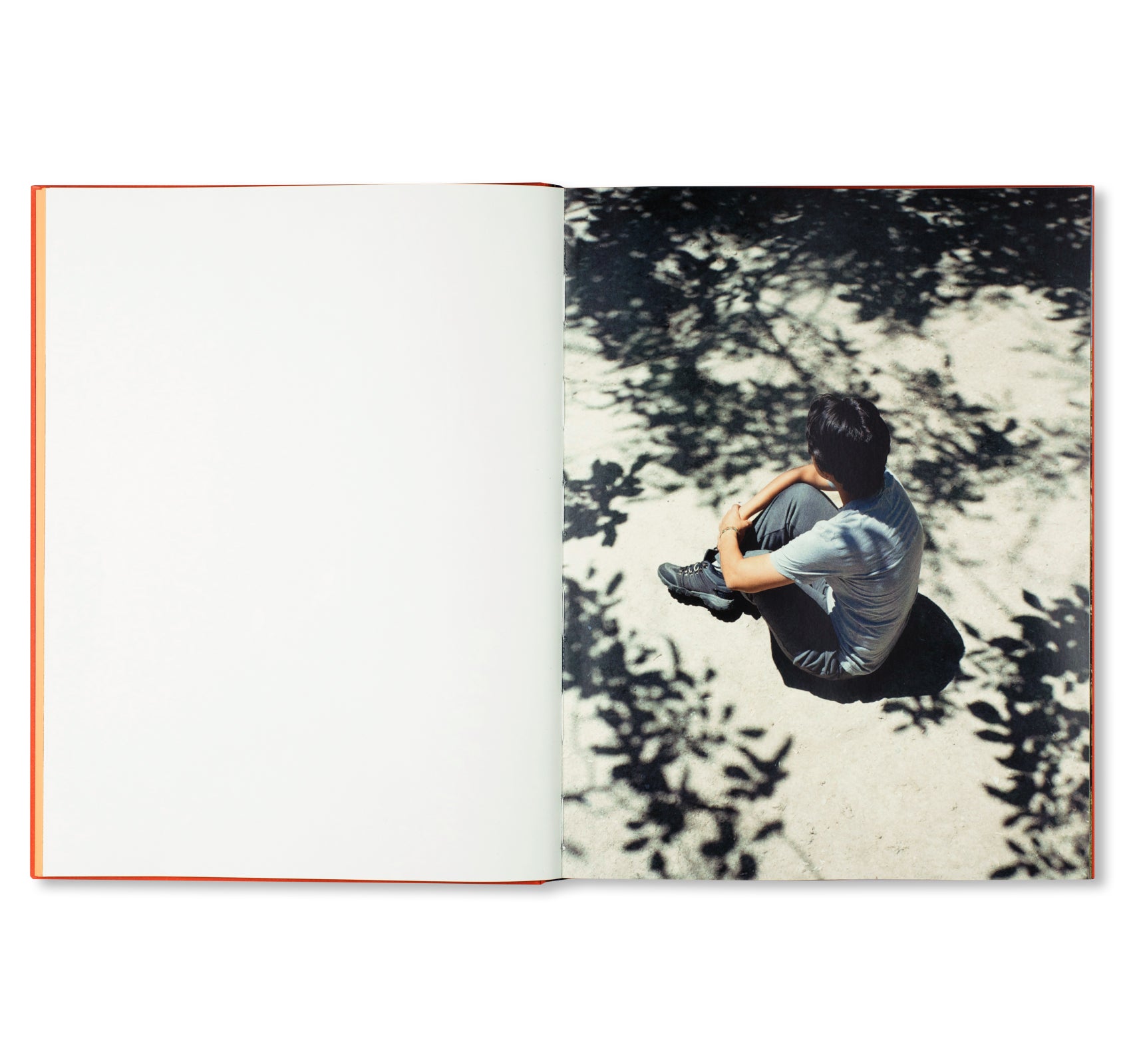

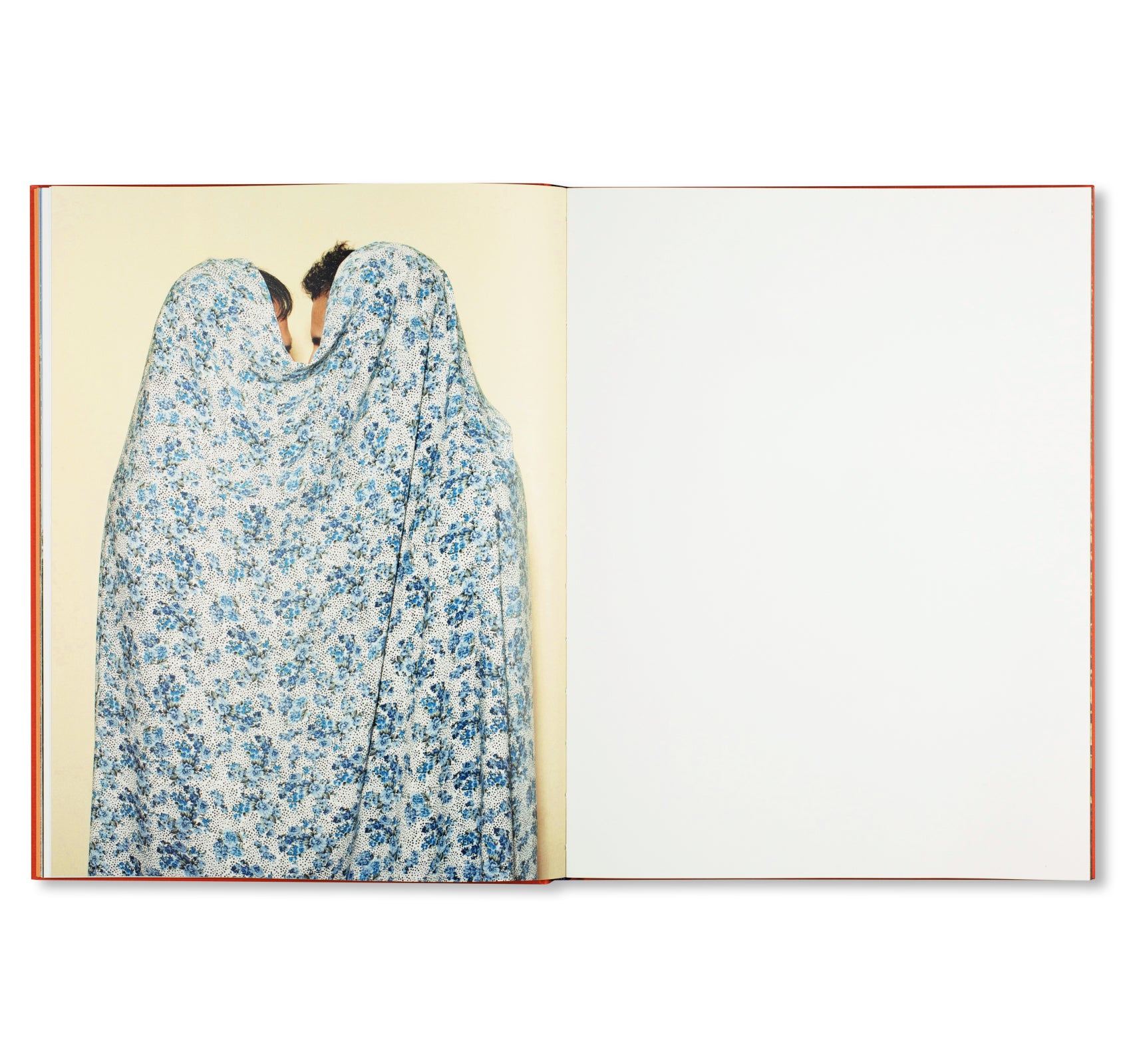

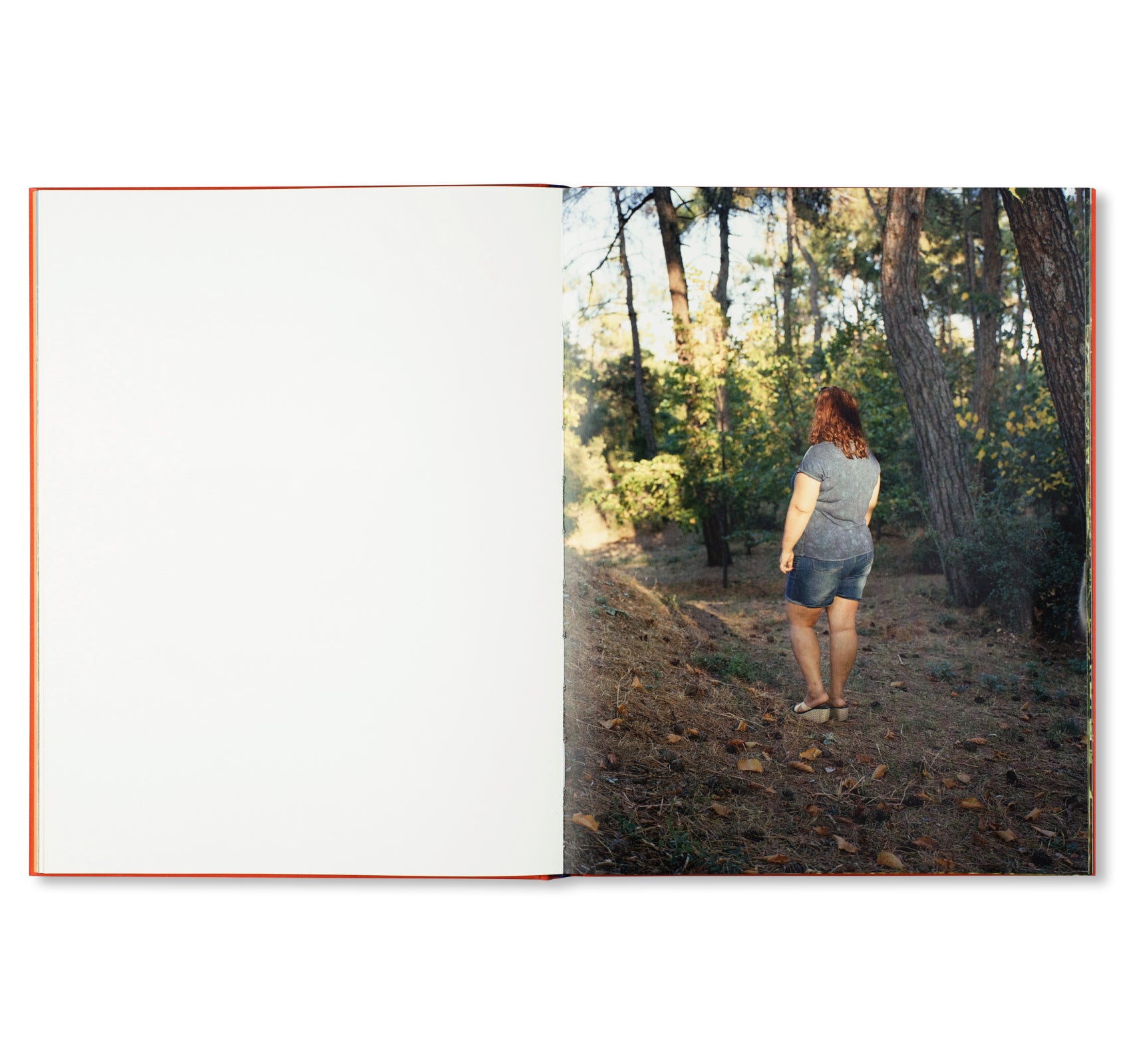

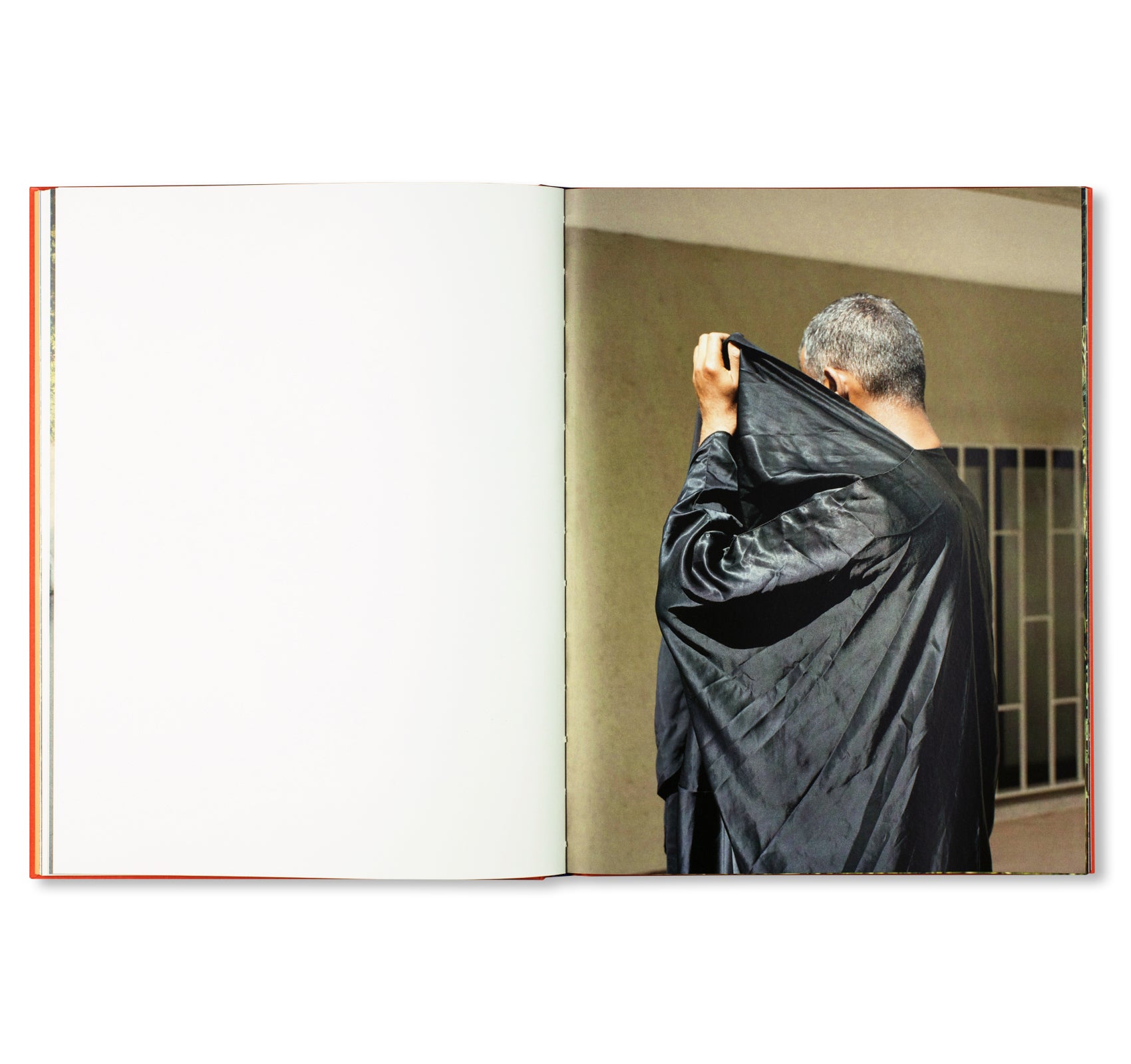

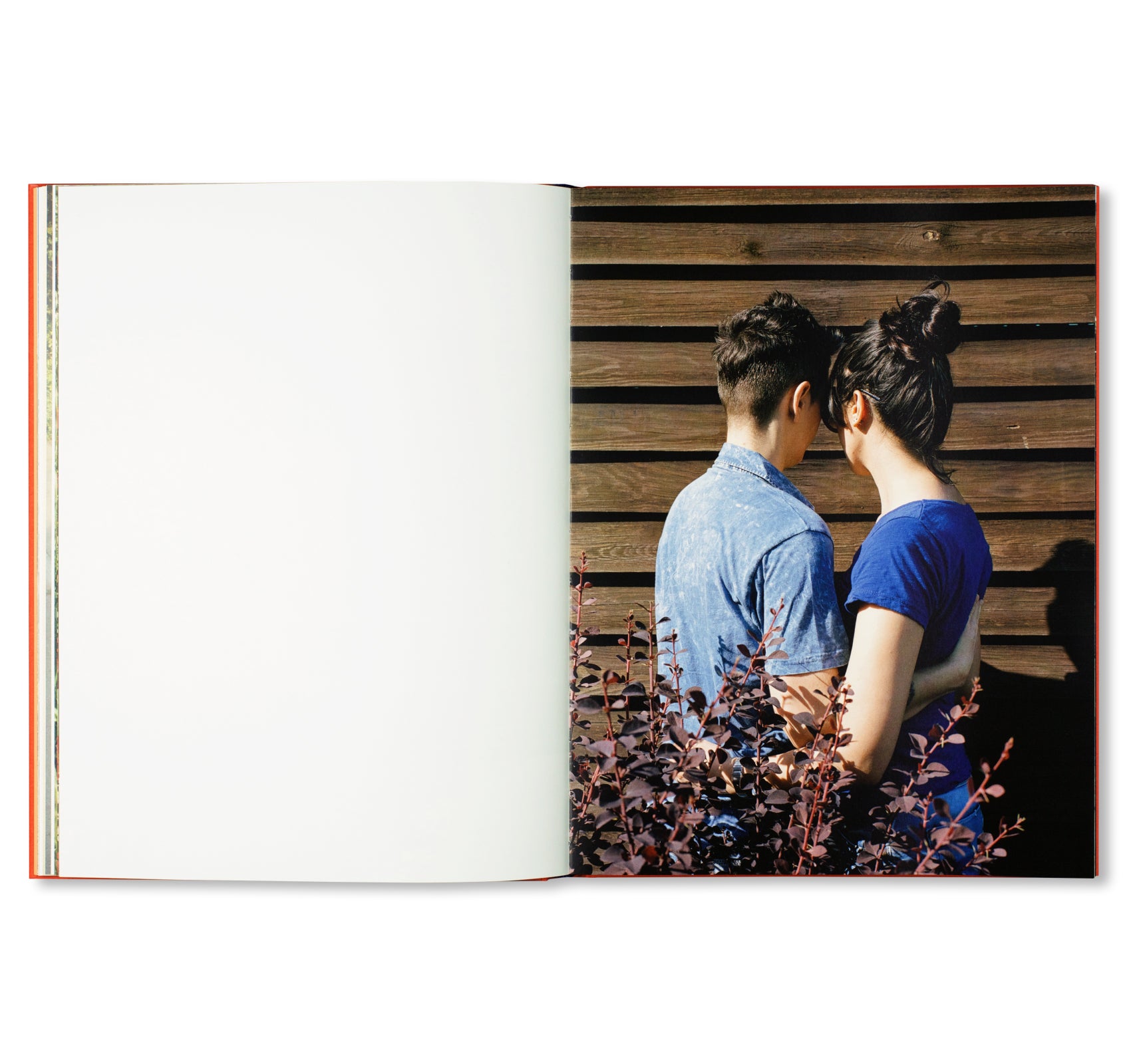

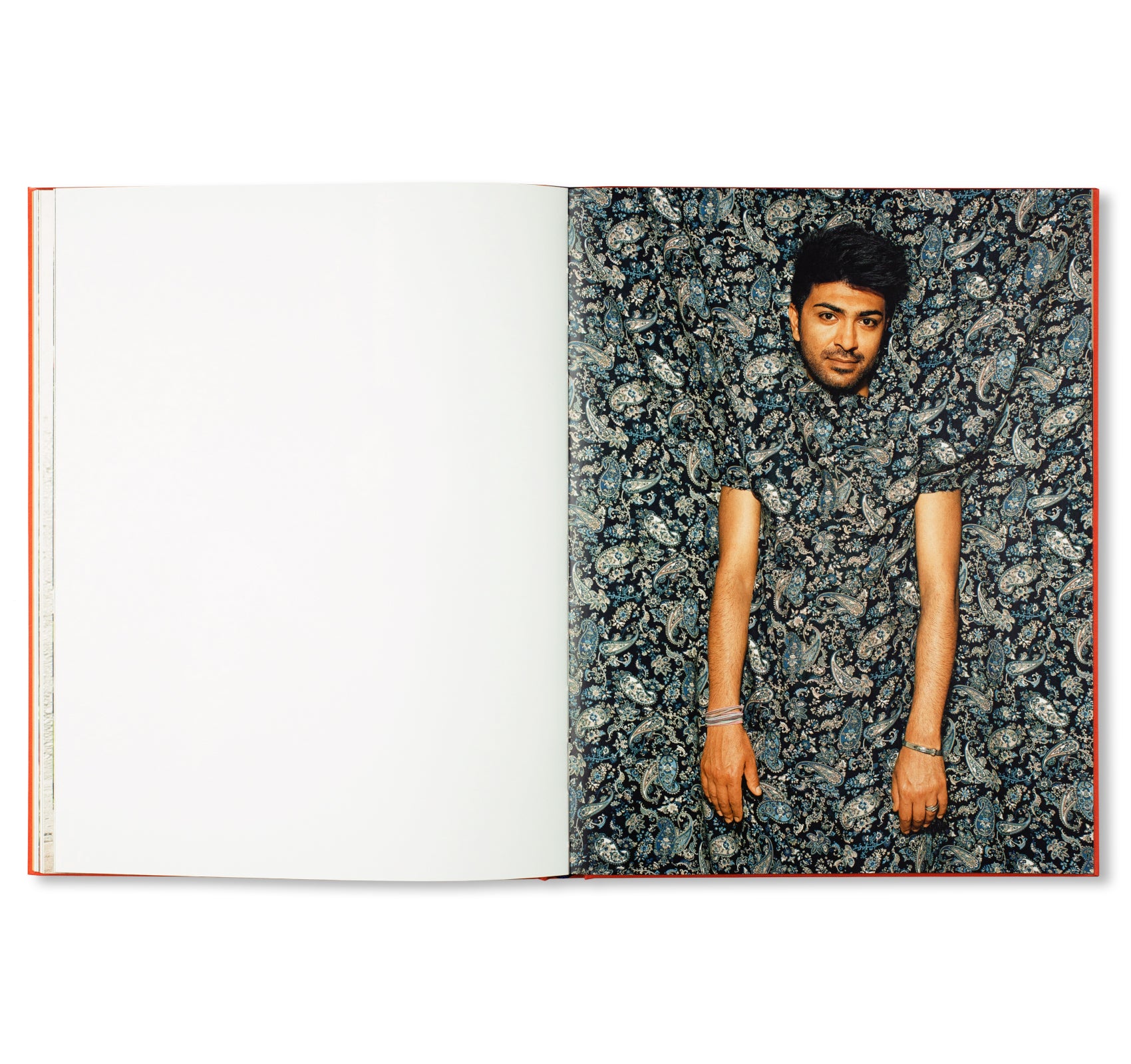

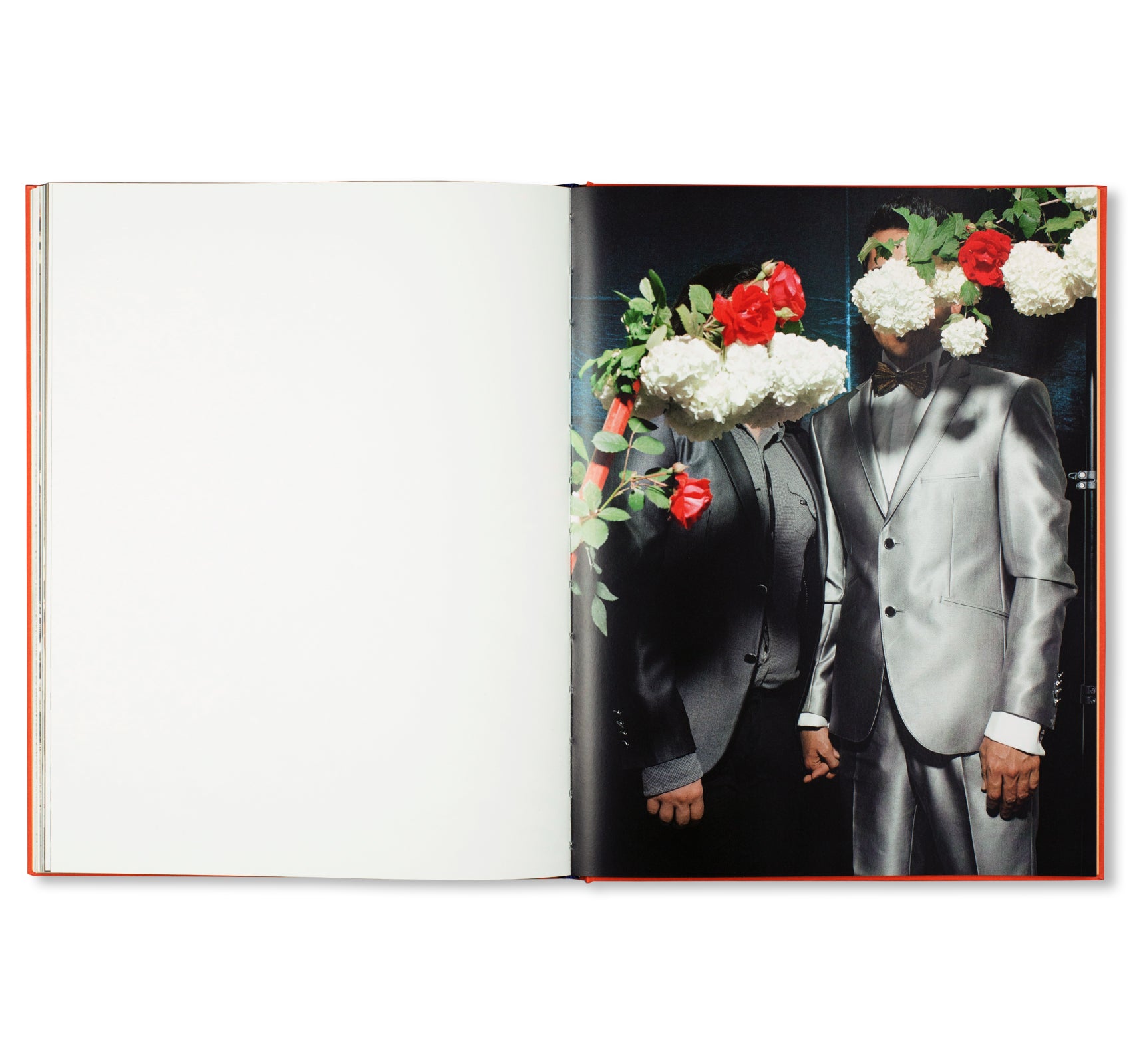

「2007年 9月 24日、コロンビア大学で行ったスピーチで当時のイラン大統領マフムード・アフマディーネジャード(Mahmoud Ahmadinejad)氏はこう宣言した。『あなたがたの国とは違い、イランにはホモセクシュアルは存在しない。』西欧諸国の多くが同性愛を公的に認め、同性婚の制度を持つ国さえあるこの時代に、イランでは今だに同性愛は死刑に値する罪であるとされ、同性愛者が性自認を公にして生きることは許されていない。残された道は、法律で認められている性転換手術を受け、性的マイノリティとして差別の対象となり続けるか、国外に逃れるか、その二つに一つである。トルコの街デニズリでは、何百名ものゲイのイラン人が LGBT難民として避難生活を余儀なくされている。彼らはここで人生を一旦保留にされ、期待してはいけないと思いながら、カミングアウトし人生をやり直すことができる第三国に迎え入れられる日を夢見ている。祖国が彼らから奪い取った顔を取り戻すために、身の安全を確保するには自分が何者であるかを隠すしかない。そのような彼らの置かれた宙ぶらりんな状況を背景に、私はアイデンティティとジェンダーというデリケートなテーマを写真で表現した。この作品は、彼らを政治的抑圧や悲惨な記憶の被害者として描いているのではない。彼らが現在直面している苦境と、性やジェンダーに対する抑圧の手が及ばないところで自分たちの愛やセクシュアリティを堂々と表現できる、より自由で良質な生き方に対して抱く希望へと焦点を当てている。軽快さとシンプルさ、楽し気に見える要素さえも織り交ぜたイメージ群は、この問題の重みや被写体が置かれている状況の危険性を逆説的に表現している。また、顔を隠した写真と顔を出した写真を交互に登場させることによって、アイデンティティが剥奪された結果生まれた心の空隙を再び満たすことの難しさを強調しているのである。」–ローレンス・ラスティ

'Speaking at Columbia University on September 24, 2007, Iranian president at the time Mahmoud Ahmadinejad proclaimed: “In Iran, we do not have homosexuals like in your country.” While most Western nations now officially accept homosexuality and some even same-sex marriage, homosexuality is still punishable by death in Iran. Homosexuals are not allowed to live out their sexuality there. Their only options are either to choose transsexuality, which is tolerated by law but considered pathological, or to flee. In Denizli, a town in Turkey, hundreds of gay Iranians are stuck in a transit zone, their lives on hold, hoping against hope to be welcomed into a host country someday where they can start afresh and come out of the closet. Set in this state of limbo, where anonymity is the best protection, my photographs explore the sensitive concepts of identity and gender and seek to restore to each of these men the face their country stole from them. My object is not to portray them as victims of political oppression and harrowing memories, but to focus on their current predicament and their hopes for a better, freer life in which to express their love and sexuality openly, beyond the reach of narrow sexual and gender dictates. The photographs paradoxically juxtapose light, simple, sometimes even festive elements with the gravity of the subject-matter and the precariousness of her subjects’ plight. Alternating between covered and uncovered faces, the series points up the difficulties these men face in reappropriating the identity space they’ve been deprived of.' (Laurence Rasti, Carouge 2016)