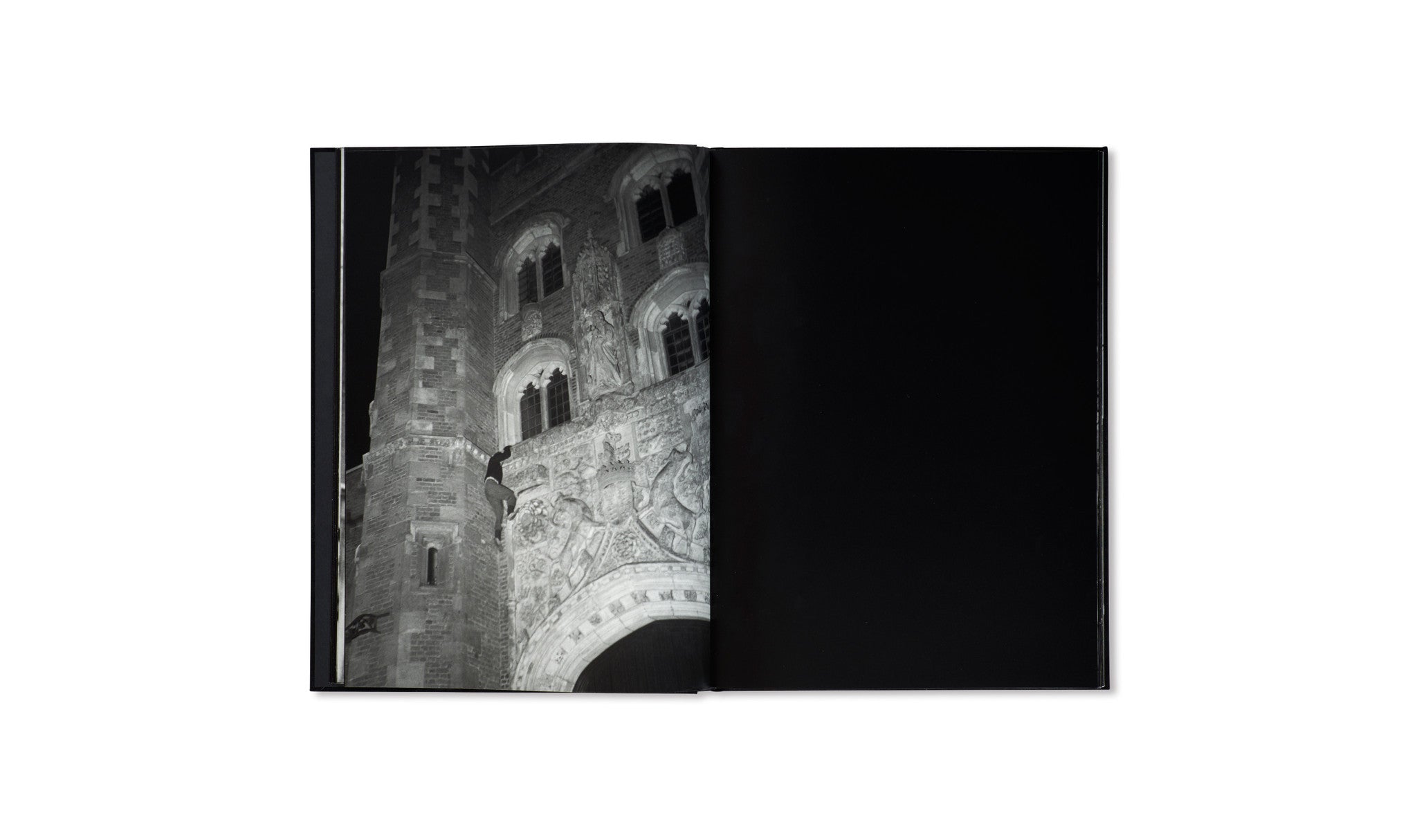

THE NIGHT CLIMBERS OF CAMBRIDGE by Thomas Mailaender

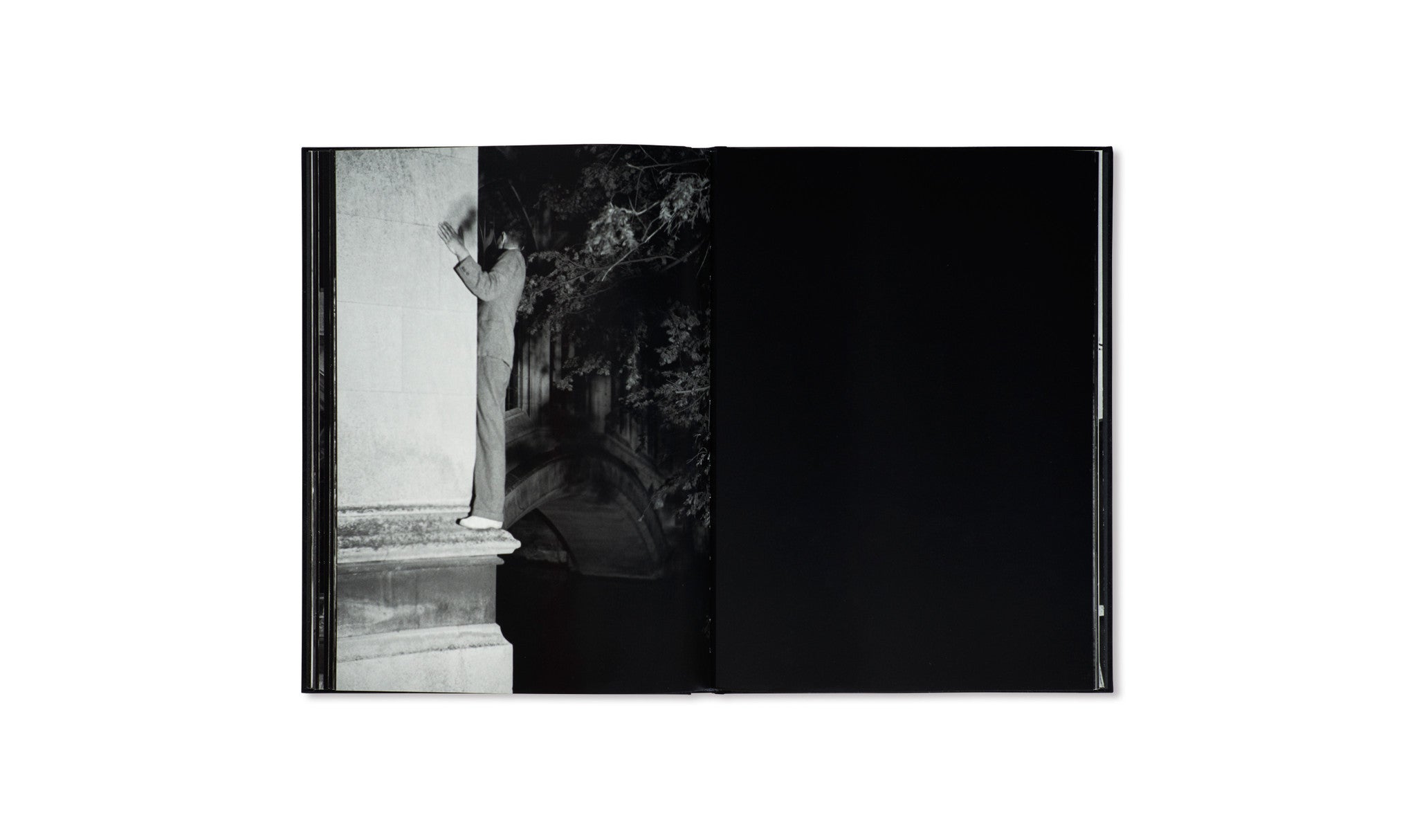

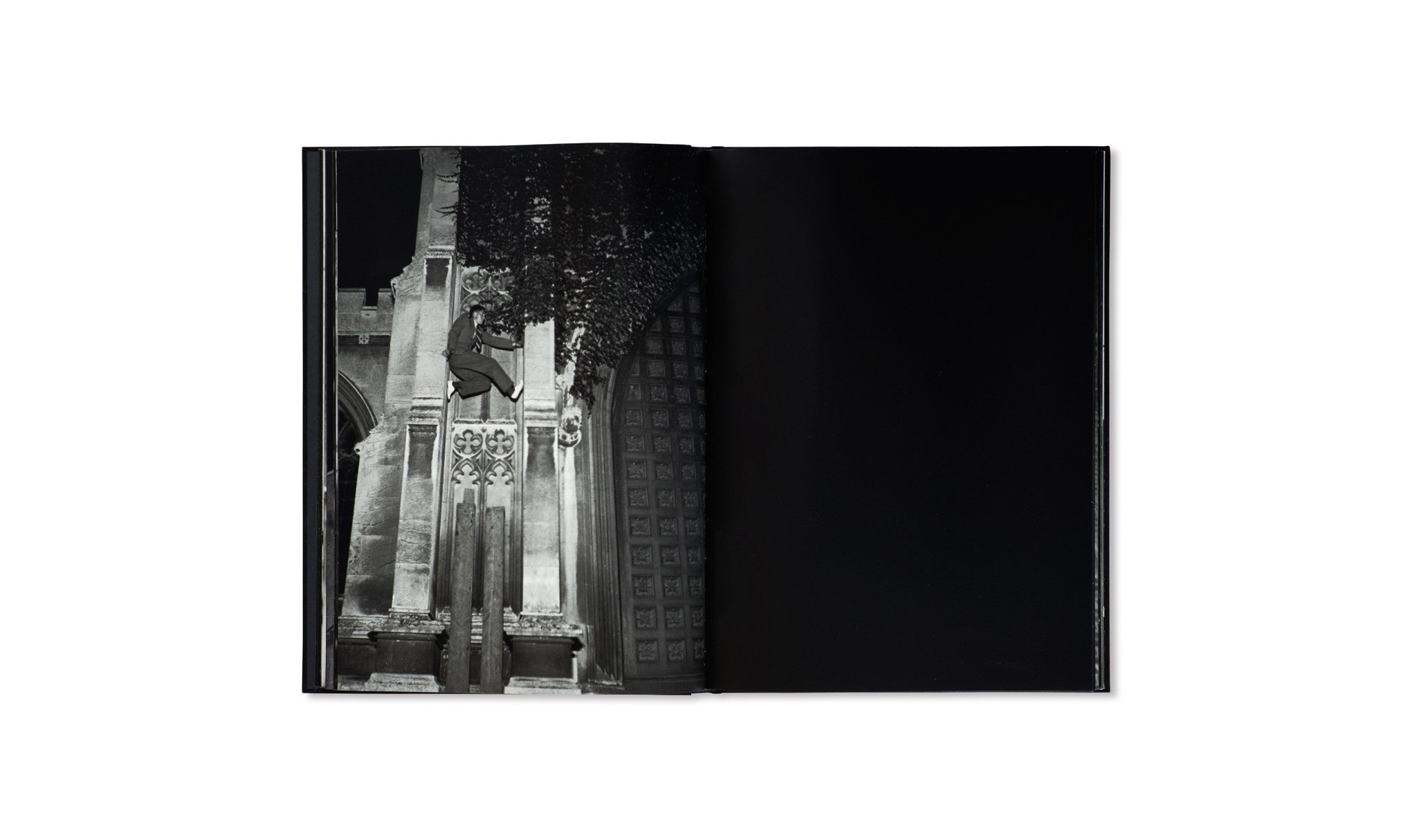

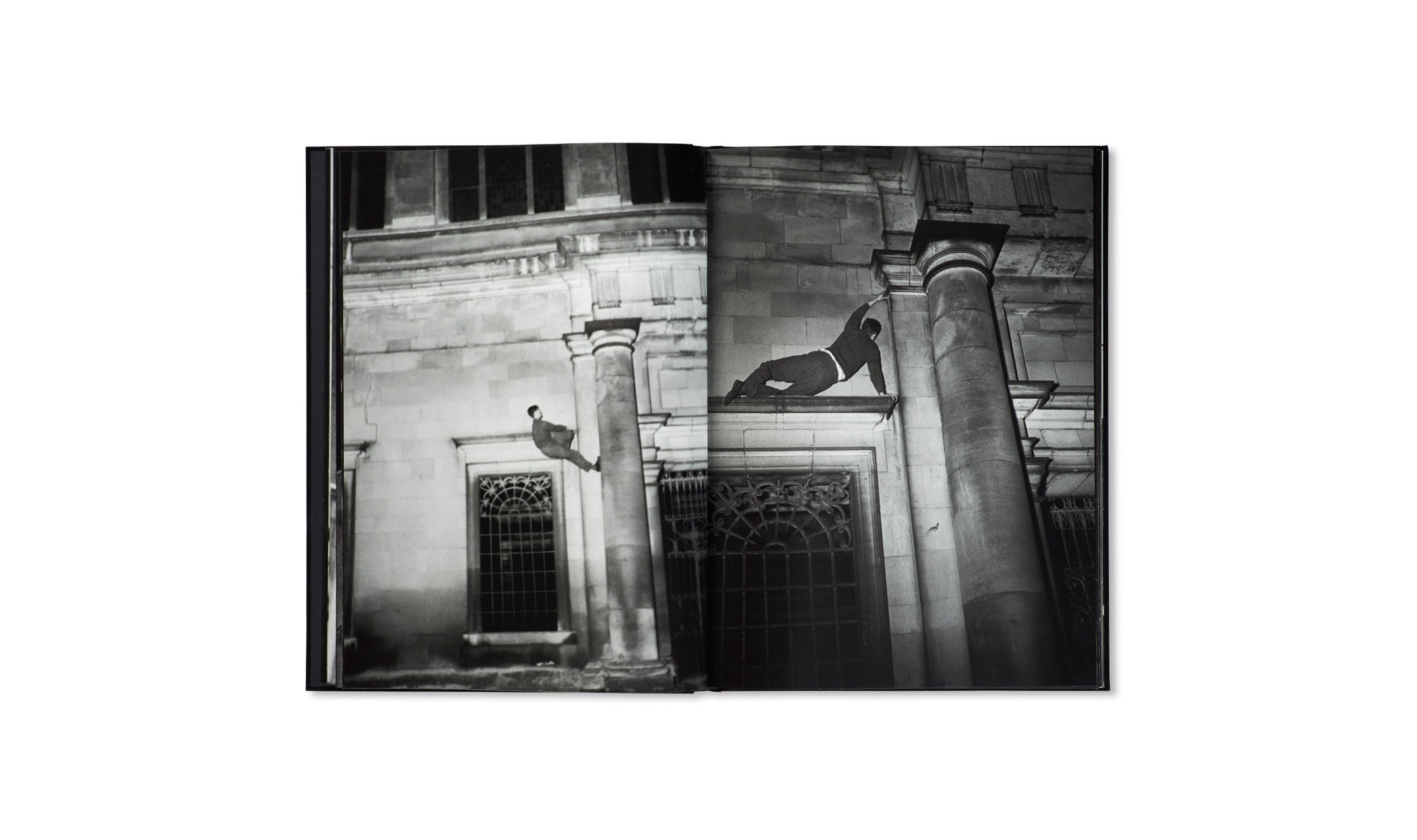

フランス人フォトグラファー、トーマス・マイレンダー(Thomas Mailaender)の作品集。本書は1922年に初めて英訳されたプルーストの作品を世に送り出したことで知られる一流出版社「Chatto & Windu」によって1937年に出版された。オリジナルは奇書中の奇書として知られており、著者のノエル・ハワード・サイミントンによって夜中に大学の壁をよじ登る学生たちの姿が写真ととも綴られている。壁を登るその行為自体は当時目新しいものでもなかった。かの有名なアルピニストであるジェフリー・ウィンスロップ・ヤングも壁に登った人物の一人であり、1899年に”登攀者のトリニティーへのガイド” という本を執筆している。サイミントンと彼の仲間たちが革新的であったのは、自ら壁登りをする様子を撮影していたという点であ る。彼らはカメラを提げて壁を登り光量不足を補うためにライトを使ったが、それは作中にも見物人として登場する警官達の注意を引いた。結果的にそれは彼ら登攀者と通行人たちが共同で演出を担う実験的かつ挑戦的なものとなり、それは当時同時期にドイツとイギリスの報道機関の間で普及していた演出された写真、ルポタージュそのものであった。参加者はほとんど互いのことも知らず、また登山やロッククライミング固有の競争優位も持たずにただ楽しみのために壁を登った。記録が残されとしても個人にとどまり、その行動や記録を統制する協会といったものも存在することはなかった。本書は作者がサイミントンの息子からオリジナルの写真を購入し、AMCと共に制作・出版された初めてその写真にフォーカスを当てた写真集である。印刷、修復技術の向上により写真はより鮮明になり、時代を超えたリアリティとロマンを鑑賞者に与えることに成功している。随所に挟まれた当時のオリジナルプリントを模したペー ジも効果的に彼ら若者たちの秘密の冒険の軌跡を辿る道しるべとなっており、歴史的価値があるだけでなく奇妙で滑稽なイギリス人 の姿を巧妙に描いた1冊にまとまっている。

The Night Climbers of Cambridge was published in 1937 by Chatto & Windus, a reputable house that had brought out the first English translations of Proust in 1922. The author was Noël Edward Symington, who went under the name of Whipplesnaith – an alias that combined the Middle English verb whipple, meaning to move around quickly, with an old Norse term for a piece of ground. The idea was that Symington and his accomplices moved quickly around the walls, roofs and spires of the colleges of Cambridge. They kept clear of commercial properties because those were in the public domain – where penalties might be incurred. Amongst the colleges they had only to cope with procters and the police, who didn’t take their misdemeanours too seriously. Climbing on the walls and roofs of colleges was nothing new. Geoffrey Winthrop Young had written a Roof-Climber’s Guide to Trinity in 1899 as well as Wall and Roof Climbing in 1905. One had to watch out for crumbling stonework and for loose fittings around pipes and guttering. Advance planning was also necessary, for the climbing had to be carried out at night to be safe from guardians of property. It was enjoyable work in itself, but it also put Symington and his friends in touch with the man in the street, most often a policeman who turned up trumps in a tight spot at 3 am. What was a novelty, though, was that Symington and his accomplices took photographs of themselves in action. These were, after all, formative years in photo-journalism. The climbers carried cameras and used lighting, which, of course, alerted the police, who sometimes feature as interested onlookers. The result is a staged photography, at a time when staged events were commonplace in both the German and the British press – reportage being a collaborative venture in which friends and passers-by acted parts. In London Bill Brandt, a photographer brought up in Germany, specialised in just the kind of staged documentary attempted by the Cambridge climbers. Even so, Symington and his friends had a point of view, downplayed but still spelled out at length in the original publication, in a separate section called ‘Chiefly Padding’. Night-climbing was a low-key activity, made up of nothing more than ‘a string of disconnected incidents’. The participants hardly knew each other, and climbed for the fun of it without the competitive edge that characterised mountaineering and rock-climbing proper. Records were kept, if at all, by individuals, and there were no societies of roof-climbers to regulate behaviour and keep the score. Symington’s night-climber was a secretive, romantic creature, like a character from Buchan ‘crossing a Scottish moor on a stormy night’. Thomas Mailaender, the contemporary artist who acquired the Cambridge climbers’ archive, identifies the night-climber as a prototype – a wary traveller, mixing with others whilst attempting to make his way across a chancy terrain without much in the way of rules and etiquette.